Look at the ten highest-performing stocks for the last twelve months. Discuss with a friend whether any of them show signs of being stuck in the innovator's paradox.

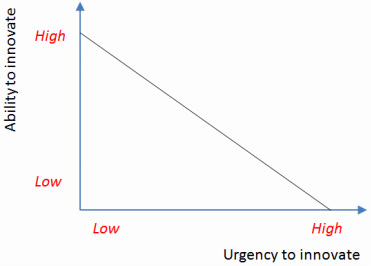

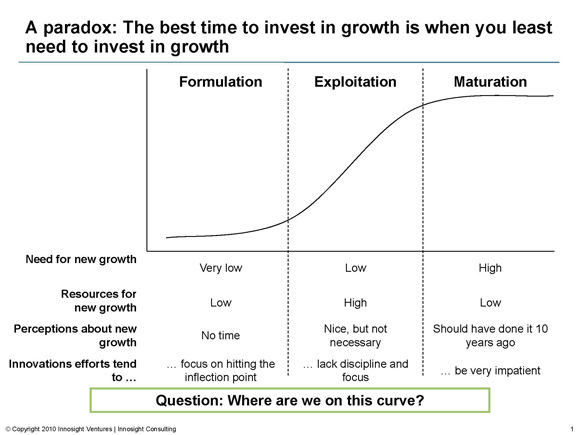

The above is one of the first exercises in the 28 day innovation regimen presented by Scott D. Anthony in his ever-readable book, The Little Black Book of Innovation. I will quote him to give his description of what this paradox actually is: "Here's the problem - by the time it was clear to everyone that [distressed companies] had to change, change was much more difficult. I call this the innovator's paradox. When times are good, you have the ability to do things differently, but not urgency or desire. When times are bad, you urgently need to do things differently, but it's punishingly hard."Anthony goes on to explain that this is the case because companies are so used to operating in their core traditional business model that they feel these tried-and-true methodologies will help reinvent themselves through innovation. Their core strategies effectively become the proverbial hammer to which everything starts to look like a nail. And innovation is no ordinary nail. In fact, it's likely not a nail at all - innovation takes place in largely uncharted territories, facing many unknowns that may share little to no resemblance to the core business. And therein lies the paradox: as the urgency to innovate increases (usually brought on by the increased pressure from competition and investors), the business shovels more resources at its core operations because this is its comfort zone. In needing to grow, the business invests more into its old way of doing things (i.e. the core business), reducing the resources available for true innovations in the new and uncertain environment, and thus, paradoxically hampering its growth opportunities! In 2001, Jim Collins' widely popular Good to Great chronicled the rise of 11 companies to Wall Street darling status. But if the last decade has taught us anything, it's that the business has been highly turbulent, with many traditional industries and business models of yore becoming disrupted to their core (e.g. the disruptions to the book publishing industry makes a fascinating read). Most of those companies moved from good to great to ... meh. With some gloriously tanking, such as Circuit City and Fannie Mae. It is more important than ever for businesses to be on their toes in these rapidly changing and unpredictable waters. They cannot afford to be caught in an innovator's paradox, wasting precious limited resources on outdated competencies, operations, business strategies and methodologies all of which are non-applicable to innovations. The true innovator needs to break out of this paradox by recognizing that innovation happens in an uncertain climate that commands radically different processes. I will devote a future write-up to what these radically different processes may look like. Back to Anthony's challenge. In order to try to hone my innovation skills I have decided to chronicle my attempt to identify whether some of 2012's top North American stocks are caught in an innovator's paradox or not. In the interest of time and space, instead of picking 10 stocks, I will pick 5 stocks that are traded on the TSX and/or Dow Jones which have enjoyed the largest year-to-date stock price increases. My sources will be Fortune's write-up of the top stocks of 2012 and The Globe and Mail's similar contribution. I will use this graph put together by innovation consulting firm, Innosight, to assist me in identifying which stage the companies are at: Will these companies go from great to bust? Or are they innovating at an opportune time that sets them up for further success? Stay tuned for next's week's write up! I encourage you to chime in as well.

Happy New Year!

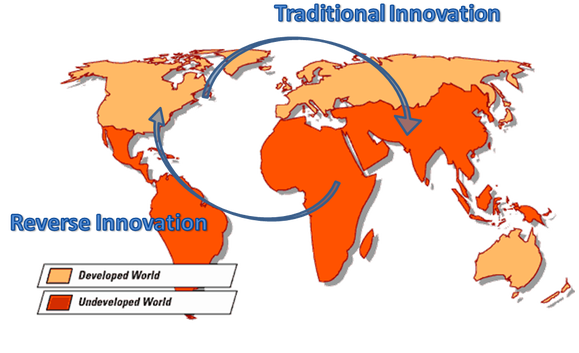

Once in a while you come across a concept or idea that is simple yet is so starkly beautiful in its potential to influence positive change that you can't help but share it with others. Today, that new concept for me was called Reverse Innovation. Traditionally, innovation was seen to originate mainly from developed nations. The products that came out of such innovations were targeted at consumers who were generally in those developed nations. Hence, corporations and managers tended to avoid expanding into emerging nations because the majority of the their population was thought, rightly, to have been too poor or too remote to purchase that corporation's products and services. Reverse innovation challenges this mindset and mode of operation, asserting that they are vastly outdated and unsustainable in today's rapidly changing global landscape. Much like C. K. Prahalad's revival of the concept of the Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid, proponents of reverse innovation cite that today's corporations' biggest opportunity to reap great rewards lies with the vast number of people who have yet been tapped into: the majority of people in emerging nations. In other words, rough 5 billion people. So how can this be done? Corporations need to innovate in order to bring to emerging markets products and services that are ultra-low cost, durable, transportable and that have impact on the lives of the multitude of people who are living below their means. Scott Anthony, of global innovation consulting firm Innosight, gives the example of ChotuKool, an India based appliance manufacturer that introduced a battery-powered and transportable cooler that has converted non-consumers of refrigerators into consumers of a much more suitable and affordable alternative. By innovating in emerging markets, corporations can then apply the lessons learned into bringing those innovations back to their own developed markets, reinventing themselves and staying on the cutting-edge of competition. Innovation expert, Vijay Govindarajan of Tuck School of Business, gives the example of Maggi noodles; developed by Nestle primarily in and for the Indian subcontinent, it has provided huge returns for the company in developed nations as well (I should know - Maggi noodles form more of a part of my paltry student diet than I care to admit!). Do take a moment to view Govindarajan's highly illuminating talk here: In closing, I want to transcribe some words from the above talk that resonated strongly with me and should also resonate strongly with the inner innovator and entrepreneur in you:

"Keep the cost of failure cheap - then you can fail more often. Failure is nothing more than converting assumptions into knowledge. Fail early, fail fast, fail cheap, so that you can galvanize behind a workable business model."

So why innovate at all? This blog post is not meant to be academically sound or thoroughly researched. It's more of a stream of consciousness in which I try to list out as many benefits of being innovative as I can. To provide at least a little structure, I've decided to break out the target of the innovation, i.e. the end-user of the innovation who will directly receive the associated benefits, into three groups: 1) The Business, 2) The Customer, and 3) The Society (aka the country, government or general economy). The Business - Remains relevant and competitive

- Identifies new growth opportunities

- Increases profits / revenues

- Reduces costs

- Attracts / Retains talent

- Remains on the cutting-edge | The Customer - Gets access to new and improved products and services

- Receives products/services faster than before

- May benefit from savings of money and/or time

- Enjoys higher standard of living | The Society - Progresses economically

- Fosters further innovation, setting in motion a virtuous cycle

- Creates more jobs and opportunities for people

- Works "smarter not harder" leading to productivity gains

- Becomes insulated from exogenous shocks to the system, i.e. it becomes self-reliant | What do you think of the above? Have I played up the benefits of innovation too much? Not enough? Are there any glaring mistakes or omissions?

Please add your comments below!

Lets face it: being called an "innovator" can sound pretty cool ( unless you're a Muslim cleric). Don't be fooled into thinking that you can only be born an innovator, though, for there are ways to measurably become one, argue innovation think-heads Dyer, Gregersen, and Christensen in their insightful book, The Innovator's DNA. Over 8 years of researching hundreds of entrepreneurs and innovators at the top of their game, the trio have decomposed the essence of the successful innovators to, what else, personality traits. The five they delve into are below: - Associating

- Questioning

- Observing

- Networking

- Experimenting

The book goes into these in a fair amount of useful detail, but the gist of it can probably be summed in as such: innovators with impact are not made overnight but rather are the product of continuous communications with both strangers and friends, the challenging of status-quos, and the relentless pursuit of getting their ideas tested and (in)validated. I couldn't help but see the similarity with Steve Blank's proverbial "getting out of the building" model. I think one other trait I would venture (no pun intended) to add here is good old fashioned courage. I feel that while all the above 5 traits are essential ingredients to make a good innovator, without the courage to step into uncharted territory and to challenge prevailing ideas, your forays into innovation can collapse and worse, your morale may take serious hits, hindering any future potential trials at innovating. So, can you become an innovator extraordinaire? There is mounting evidence from the top thinkers in this space to confidently suggest that you can. Be courageous. Talk to people about their pains and frustrations. Look to successes in different industries to see if you can transfer them to your own. Invest in upping your public-speaking and communication skills. Trust yourself. Test your assumptions vigorously and be brutally honest with yourself. In closing, I'd like to share a video interview that the Canadian Innovation Center had with two of the authors of The Innovator's DNA.

In the words of Dr. Hal Gregersen: We don't have to be famous to get great results - we just have to engage [in] the actions [listed above] in order to get the same sorts of [innovations] happening.

...with some exceptions, Canada does not take the steps that other countries take to ensure science can be successfully commercialized and used as a source of advantage for innovative companies seeking global market share. Canadian companies are thus rarely at the leading edge of new technology and too often find themselves a generation or more behind the productivity growth achieved by global industry leaders. - The Conference Board of Canada (Full report)

Earlier this year, the Conference Board of Canada gave the country a grade of "D" in innovation, placing it at an astounding 14th place out of 17. As subjective as these kinds of rankings might be (how were the 17 countries picked and why those countries specifically?), it is hard to deny how underwhelming a picture this paints for any country.

But lets take a step back. Even better, lets swing a few miles back.

Just what exactly is innovation? Why should we care? Why do governments care? Why has "innovation" become a favorite buzzword on the blogosphere again? Wait ... has it?

A quick look-up on Google Trends shows some interesting results: 1) According to Google's indexing and crawling of webpages around the world, the overall frequency of the term "innovation" has actually not increased. In fact, it looks like there may, arguably, be a slightly decrease in the usage of the term. And,

2) There is a very clear saw-toothed pattern in the frequency of the usage of "innovation", or at least the usage of the specific word on the Internet. To venture a bit further, it appears the peaks tend to be in the final quarter of the year, usually in the months of October and November, followed by sharp troughs in December and occasionally mid-year. If we were to believe in this pattern, I would predict that the first few months of 2013 will see a sharp jump upwards. Watch this space!

So then, given the saw-toothed nature of the above graph, is innovation a cyclical or seasonal phenomenon? Do people only seek it at specific points of the business cycle? Is it predictable? I admit, these are all questions that I have only begun to ponder about, so I'm afraid I don't have the answers to them. As future innovators, however, I believe it is worth our while to consider them.

Hang on, I'm getting ahead of myself again - we still haven't defined "innovation". Here's how the Conference Board of Canada defines it:

Innovation is the ability to turn knowledge into new and improved goods and services.

Sounds simple enough, right?

Lets take a look at how a few others see innovation:

"The carrying into effect of an innovation involves, not primarily an increase in existing factors of production, but the shifting of existing factors from old to new uses." - Joseph Schumpeter

"Innovation is the process of change that creates and grows wealth." - Roger More, Professor of Marketing at Richard Ivey School of Business

"Innovation is the specific tool of entrepreneurs, the means by which they exploit change as an opportunity for a different business or a different service. It is capable of being presented as a discipline, capable of being learned, capable of being practiced." - Peter Drucker

"A new method, idea or product." - Oxford Dictionary

And on, and on. The fact of the matter is that is it quite easy to get ahead of oneself when discussing innovation because it can mean different things to different people and sources of authority and in different contexts. Even Schumpeter, regarded widely as the Prophet of Innovation, was criticized for his flip-flopping views and definitions. While some might say that his perspectives were highly context-specific, others may argue that he too struggled to wrap his hands around the slippery beast that is innovation. I think there is truth to both explanations, but that will probably be left for another blog post.

To switch quickly back to the issue of Canada, I know I started this blog on a bit of a glum note. The full report from the Conference Board of Canada isn't all that chipper either. That said, I wanted to mention that the report does present a silver lining:

"On a small scale, however, Canada has demonstrated it is capable of developing innovation strategies to successfully align business, government, investors, and customers."

I believe there are many valuable lessons to be learned from these "smaller" successes. Anything that we can do to learn about innovative wins on smaller scales has the potential of helping us on a larger scale as well.

In this weekly blog, I hope to share and discuss my musings on what I find interesting and topical about the world of innovation. I am, in particular, interested in technology, business strategy and the relevance of innovation to Canada and its broader macroeconomic context. If you share these interests as well, I hope you follow me and find my posts interesting and perhaps even educational. If you don't have any interest in the aforementioned topics, and you've read this far, then I can only assume I did something right and that I can change your mind!

Happy innovating.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed